I’ve been house-sitting for a friend who lives in Burnt Oak, which you would expect to be a solidly suburban area, lying as it does in far North London, nearly at the end of the Northern Line. But Burnt Oak feels metropolitan and is very multicultural. At Sunday lunchtime, I wandered around the huge Turkish grocery, Broadway Food Centre, to find piles of Romanian sausage, dozens of Greek cheeses, racks of plantains, Indian spices and pulses… and people of the corresponding nationalities and more all purchasing food for the week.

The range of flours rivaled that of the vast Kensington Wholefoods and was completely different: many different grades of Eastern European-origin wheat flour and Afro-Carribbean and Indian specialities like cassava, chickpea, yam, chapati flour. I bought a bag of fine semolina (aka durum wheat), which I’ve been after for ages for Daniel Leader’s pane di Altamura recipes. But I didn’t have the book with me, so I made this recipe instead.

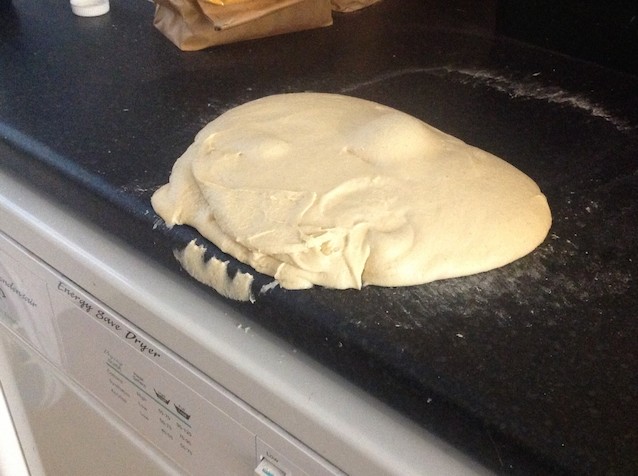

Photo: Sonya Hallett.

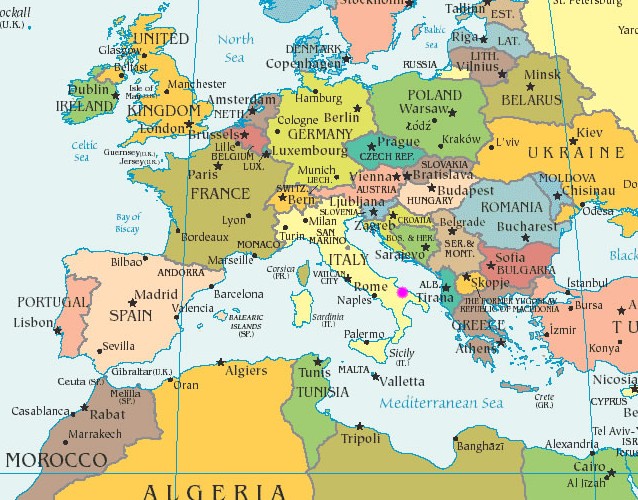

First I should explain why pane di Altamura is so special. It comes from the small town of Altamura in Southern Italy, indicated very approximately with a pink dot below, with a population of just 70,000. The bread is distinctive enough to have gained PDO status. There are plenty of rules about hydration and percentages one has to follow in order for the bread to be certified (and this blogger has had a go at fulfilling them), but the over-riding characteristic is that the flour is largely durum wheat, which is usually used only for pasta-making, as well as having a dry-ish dough, sourdough leaven and a mighty thick crust. Altamura’s local food culture is also so strong that it killed MacDonald’s.

I look forward to making it now the book and I are reunited.

Now, the recipe I used for this, I don’t think it was even trying to imitate pane di Altamura, because it had sesame seeds on top. I think it’s a general Italian semolina bread instead. No matter, it was delicious. Also, it was quite distinct in taste from bread made with usual wheat flour: dense and sweet-smelling even though there was no sugar in it, with a texture that was halfway between bread and crumpet. I would certainly make this again, if I didn’t have another 81 loaves to go!

Here’s the crumb:

And here’s how to make it.

Ingredients:

1 cup lukewarm water

1tsp active dry yeast

1.5 cups semolina flour

1 cups bread flour

0.5 tbsp salt

1 egg, to glaze

olive oil, for bowl

sesame seeds

Method

1. Mix the yeast into the water, then add the semolina flour. As Macheesmo points out, it will looks remarkably like scrambled egg.

2. Mix in the bread flour to form quite a firm dough. Leave it to rest for 10 mins, then knead until smooth. The original recipe suggests you might want to add more flour if it’s sticky; I am actually added a dribble more water, because I am always afraid of dry bread.

3. Coat the dough with olive oil and leave to rise until it triples in size. This will take longer than usual for a yeast loaf, because you haven’t added much yeast. Mine took three hours.

4. Shape the bread, place on a baking tray, cover and leave it again, to double in size this time. Preheat the oven to 220 degrees.

5. When the bread’s ready to bake, brush well with beaten egg and scatter on the sesame seeds. Give it a few diagonal slashes.

6. When you put the loaf in the oven, turn the heat down to 190. Bake until cooked through and golden on top, 30-40 minutes.